The coat of arms and flag are unchangeable symbols of any modern state. The beginnings of heraldry appeared in ancient times, in the Middle Ages it became the property of every noble house, and in modern times it was firmly established as a mandatory attribute of all countries of the world.

In terms of having its own symbols, the RSFSR, a state entity that existed from 1917 to 1991, was no exception. It was the predecessor of the modern Russian Federation. But, before considering the attributes of this republic, let's figure out what it was. How does RSFSR stand for?

The birth of the RSFSR can be dated back to 1917, when the Bolsheviks came to power in the country after the victory in the October Revolution. True, initially the name of the new state was somewhat different - the Russian Soviet Republic (RSR) or the Russian Federative Republic (RFR). The name of the RSFSR was officially established on July 19, 1918, after the Constitution came into force. A large number of other innovations were introduced then. For example, in the same year 1918, the capital of the RSFSR changed. She moved from Petrograd to Moscow.

Since 1922, Russia, along with other republics, entered where it remained until its collapse in 1991. This ended the period of the RSFSR, and the era of the Russian Federation began. It continues to this day.

Decoding the abbreviation RSFSR

But how does the RSFSR stand for? Since 1918, this abbreviation has been read as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. In 1936 the word order was changed. From then on, the name stood for Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

State flag

One of the main symbols of the state is the national flag. It is with this attribute that any country is primarily associated. The state flag of the RSFSR has undergone several significant modifications over the period of its existence.

Flag of the post-revolutionary period

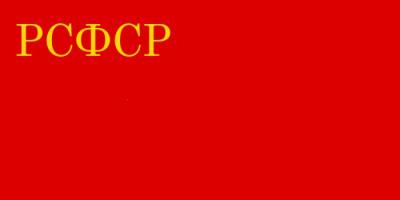

Immediately after the Bolshevik revolution, the role of the state flag was claimed with absolutely no additional images or inscriptions on it. True, this fact was not documented in any official document.

The Constitution adopted in 1918 stated that the state flag of the country would be a red cloth, in the upper left corner of which there was the inscription “RSFSR” embroidered in golden letters. There was no more accurate description of the proposed banner in the main law of the country at that time.

In 1920, a more detailed description was given in a resolution of the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. It was also indicated that the inscription “RSFSR” should be framed by a golden rectangle. This form was valid until 1937.

Banner of the Stalin era

The adoption of the new Constitution in 1937 introduced some adjustments to the state flag of the RSFSR. The development of the new version was carried out by the talented artist A. N. Milkin. In particular, the golden frame was removed, and the font of the letters was changed from stylized Old Slavic to regular. This form of the flag was officially used for seventeen years, including during the Great Patriotic War.

Flag (1954 - 1991)

In 1954, the official banner of the RSFSR was radically redesigned. The artist V.P. Viktorov took on the implementation of the new project. Now the flag included the official symbols of the USSR - the hammer and sickle, which were also located in the upper left edge. In addition, there was a light blue stripe at the flagpole. The main background of the flag remained unchanged red. All the inscriptions on the panel disappeared.

This official version of the banner lasted much longer than others (37 years) and was replaced only in 1991 by the Federation.

National emblem

Along with the flag, the coat of arms is considered the most important national symbol. This attribute has been included in modern heraldry since the Middle Ages. The RSFSR also had its own coat of arms, and during its existence it underwent no less changes than the flag.

The first official seal of the RSFSR

The coat of arms of the RSFSR began to be developed at the beginning of 1918 by a special commission. A large number of proposals immediately appeared. The commission was most pleased with the version of the artist Alexander Leo. In his design, the coat of arms represented an image in the center of which a crossed sickle, hammer and sword were placed. At the bottom there should have been an inscription: “Council of People’s Commissars.” But V.I. Lenin proposed abandoning the sword, thereby wanting to emphasize the peaceful nature of the future communist society. He also expressed a desire to replace the inscription with the motto: “Workers of all countries, unite.”

In the final version, the coat of arms of the RSFSR of 1918 was a symbol in the shape of a circle, which depicted a crossed hammer and sickle on a red shield in the rays of the rising sun and framed by ears of grain.

Coat of arms (1925 - 1978)

Already in 1920, it was decided to improve the coat of arms of the RSFSR. Immediately, work began on this, led by the artist N. A. Andreev. First of all, the full inscription “Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic” was replaced with an abbreviation. In addition, the coat of arms ceased to have an absolutely rounded shape; ears of corn framed it completely, and not just a red shield with a hammer and sickle. Some other smaller graphical changes were also made.

This form was finally enshrined in the 1925 Constitution. In this form, the coat of arms existed practically unchanged until its collapse. The exception was one small but important detail, which will be discussed below.

Another change to the coat of arms

In 1978, a new Constitution was introduced. In connection with its adoption, it was decided to bring the coat of arms of the RSFSR to the all-Union standard. This was expressed in the addition of just one detail, namely a five-pointed star at the top of the shield, in the place where the ears of grain met.

No further changes in symbolism were made until the collapse of the USSR. But even after the creation of the independent RSFSR, it served as the basis for its attributes until December 1993, when it was adopted as a state symbol. Until that time, the only difference between the emblem of the new state and the coat of arms of the union republic was only a change in the inscription with the name of the country at the top of the shield. Nevertheless, in the heraldry of the modern Russian state, absolutely nothing remains from Soviet times.

Results

Over the years of the existence of the RSFSR as an integral part of the Soviet Union, the flag and coat of arms of this state entity have experienced significant external changes. This was due to the desire to bring the symbols of individual republics closer to all-Union standards. It is worth highlighting the predominant importance of the attributes of the communist movement in the elements of the coat of arms and flag of the RSFSR.

The coat of arms was first described as follows:

“The coat of arms of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic consists of images on a red background in the rays of the sun of a golden sickle and hammer, placed crosswise with the handles downwards, surrounded by a crown of ears of ears and with the inscription: a) Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

b) Workers of all countries, unite!”

The authorship is attributed to the artist Alexander Nikolaevich Leo (this fact is not known for certain).

At the beginning of 1920, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee decided to improve the image of the coat of arms and approved on July 20, 1920 its new version, developed by the artist N. A. Andreev. The new coat of arms was finally legalized by the Constitution of the RSFSR, adopted by the 12th All-Russian Congress of Soviets on May 11, 1925.

- From May 11, 1925, the abbreviated name of the state began to be placed on the shield: “R.S.F.S.R. ", in accordance with the rules of the spelling in force at that time, and placed in the upper part of the shield, on each side the shield-cartouche was surrounded by 7 ears of corn, the motto was placed on a red ribbon at the bottom of the coat of arms.

- In 1954, according to new spelling rules from the abbreviation “R. S.F.S.R.” points have been removed.

- On April 12, 1978, in connection with the adoption of the new Constitution, a five-pointed red star with a gold border was added above the shield:

The state emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic is

On November 16, 1993, the President, by his order (No. 740-rp), appointed a commission to develop the coat of arms, the chairman of which was the chief state archivist of Russia R. G. Pihoya, the members of the commission were G. V. Vilinbakhov (head of the Heraldic Department of the Rosarkhiv), V. V. Vinogradov (Director of the Consular Service Department of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs), V.P. Egorov (Deputy Chief of Staff of the Border Troops of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and others.

Just two weeks later, on November 30, 1993, the President of Russia signed Decree No. 2050 “On the State Emblem of the Russian Federation,” which came into force on December 1, 1993 and introduced the image of the coat of arms of the Russian Federation with a double-headed eagle.

– state symbol of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1918–1992), Russian Federation (1992–1993).

History of the coat of arms.

The coat of arms was first described as follows:

“The coat of arms of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic consists of images on a red background in the rays of the sun of a golden sickle and hammer, placed crosswise with the handles downwards, surrounded by a crown of ears and with the inscription:

a) Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

b) Workers of all countries, unite!” – Chapter XVII, Section 6, § 89, Constitution of the RSFSR 1918

The authorship is attributed to the artist Alexander Nikolaevich Leo (this fact is not known for certain).

At the beginning of 1920, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee decided to improve the image of the coat of arms and approved on July 20, 1920 its new version, developed by the artist N. A. Andreev.

The new coat of arms was finally legalized by the Constitution of the RSFSR, adopted by the 12th All-Russian Congress of Soviets on May 11, 1925.

– From May 11, 1925, the abbreviated name of the state began to be placed on the shield: “R.S.F.S.R.”, in accordance with the rules of the then spelling, and placed in the upper part of the shield, on each side the shield-cartouche was surrounded by 7 ears of corn, the motto was placed on a red ribbon at the bottom of the coat of arms.

– In 1954, according to new spelling rules from the abbreviation “R. S.F.S.R.” points have been removed.

– On April 12, 1978, in connection with the adoption of the new Constitution, a five-pointed red star with a gold border was added above the shield:

The state emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic is an image of a hammer and sickle in a red field in the rays of the sun and framed by ears of corn, with the inscription: “RSFSR” at the head and “Workers of all countries, unite!” on the motto ribbon. The shield is crowned with a five-pointed star

– Article 180 of the 1978 Constitution of the RSFSR

– In 1981, the colors of the elements of the coat of arms were specified:

In the color image of the State Emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the hammer and sickle, the sun and golden ears of corn;

red star framed with gold border

– Regulations “On the State Emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic” dated January 22, 1981.

However, the modernized coat of arms did not have time to become widespread, since many forms of relevant documents with the old coat of arms remained in the country, which were widely used. There is information that a new version of the image of the coat of arms appeared in the office of the Chairman of the Supreme Council R.I. Khasbulatov, where the inscription “Russian Federation” was made in two arcs in gold letters. The inscription on the coat of arms on the rostrum of the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation was made in the same way. On some forms (postal, etc.) with a small image of the coat of arms, a coat of arms with an old abbreviation was depicted.

On November 16, 1993, the President, by his order (No. 740-rp), appointed a commission to develop the coat of arms, the chairman of which was the chief state archivist of Russia R. G. Pikhoya, the members of the commission were G. V. Vilinbakhov (head of the Heraldic Department of the Federal Archive), V. V. Vinogradov (Director of the Consular Service Department of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs), V. P. Egorov (Deputy Chief of Staff of the Border Troops of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and others.

Just two weeks later, on November 30, 1993, the President of Russia signed Decree No. 2050 “On the State Emblem of the Russian Federation,” which came into force on December 1, 1993 and introduced the image of the coat of arms of the Russian Federation with a double-headed eagle.

Rising Sun, name "Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic"; later – abbreviation “RSFSR”, and also – red star

remained in effect until 1925

Coat of arms of the RSFSR- state symbol of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1918-1992), Russian Federation (1992-1993).

History of the coat of arms

The coat of arms was first described as follows:

“The coat of arms of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic consists of images on a red background in the rays of the sun of a golden sickle and hammer, placed crosswise with the handles downwards, surrounded by a crown of ears and with the inscription:

a) Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

B) Workers of all countries, unite!”

Chapter XVII, Section 6, § 89, Constitution of the RSFSR 1918

The authorship is attributed to the artist Alexander Nikolaevich Leo (this fact is not known for certain).

At the beginning of 1920, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee decided to improve the image of the coat of arms and approved on July 20, 1920 its new version, developed by the artist N. A. Andreev. The new coat of arms was finally legalized by the Constitution of the RSFSR, adopted by the 12th All-Russian Congress of Soviets on May 11, 1925.

- On May 11, 1925, the abbreviated name of the state began to be placed on the shield: “R.S.F.S.R. ", in accordance with the rules of the spelling in force at that time, and placed in the upper part of the shield, on each side the shield-cartouche was surrounded by 7 ears of corn, the motto was placed on a red ribbon at the bottom of the coat of arms.

- In 1954, according to new spelling rules from the abbreviation “R. S.F.S.R.” points have been removed.

- On April 12, 1978, in connection with the adoption of the new Constitution, a five-pointed red star with a gold border was added above the shield:

The state emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic is an image of a hammer and sickle in a red field in the rays of the sun and framed by ears of corn, with the inscription: “RSFSR” at the head and “Workers of all countries, unite!” " on the motto ribbon. The shield is crowned with a five-pointed star

Article 180 of the 1978 Constitution of the RSFSR

- In 1981, the colors of the elements of the coat of arms were specified:

In the color image of the State Emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the hammer and sickle, the sun and golden ears of corn; red star framed with gold border

Regulations “On the State Emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic” dated January 22, 1981.

In this form, the coat of arms existed until May 16, 1992, when Law of the Russian Federation of April 21, 1992 No. 2708-I, adopted by the 6th Congress of People's Deputies, came into force, which eliminated the discrepancy that existed at that time. On December 25, 1991, Law of the RSFSR No. 2094-I “On changing the name of the state “Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic””, adopted by the Supreme Council of the RSFSR, came into force, according to which the state officially received a new name “Russian Federation” (no longer “ socialist"), however, on the coat of arms, in accordance with the current constitution, the abbreviation of the old name “RSFSR” continued to appear.

- In accordance with the innovations of 1992, according to the new wording of Article 180 of the Constitution, the words “Russian Federation” should have been placed at the top of the coat of arms.

However, the modernized coat of arms did not have time to become widespread, since many forms of relevant documents with the old coat of arms remained in the country, which were widely used. There is information that a new version of the image of the coat of arms appeared in the office of the Chairman of the Supreme Council R.I. Khasbulatov, where the inscription “Russian Federation” was made in two arcs in gold letters. The inscription on the coat of arms on the rostrum of the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation was made in the same way. On some forms (postal, etc.) with a small image of the coat of arms, a coat of arms was depicted with the old abbreviation.

On November 16, 1993, the President, by his order (No. 740-rp), appointed a commission to develop the coat of arms, the chairman of which was the chief state archivist of Russia R. G. Pihoya, the members of the commission were G. V. Vilinbakhov (head of the Heraldic Department of the Rosarkhiv), V. V. Vinogradov (Director of the Consular Service Department of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs), V.P. Egorov (Deputy Chief of Staff of the Border Troops of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and others.

Just two weeks later, on November 30, 1993, the President of Russia signed Decree No. 2050 “On the State Emblem of the Russian Federation,” which came into force on December 1, 1993 and introduced the image of the coat of arms of the Russian Federation with a double-headed eagle.

Gallery

see also

Write a review about the article "Coat of Arms of the RSFSR"

Notes

- On July 10, 1918, at the final meeting, the 5th All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers', Peasants', Soldiers' and Cossacks' Deputies adopted the first Constitution of the RSFSR, which officially approved the first coat of arms of the republic. Officially, the Constitution of the RSFSR of 1918 came into force on July 19, 1918.

- Regulations “On the State Emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic” dated January 22, 1981.

- Law of the Russian Federation of April 21, 1992 No. 2708-I // Gazette of the Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR and the Supreme Council of the RSFSR. - 1992. - No. 20. - Art. 1084. This law came into force from the moment of publication in the Rossiyskaya Gazeta on May 16, 1992.

- The Supreme Council of the RSFSR approved the Law of the RSFSR of December 25, 1991 No. 2094-I // Gazette of the Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR and the Supreme Council of the RSFSR. - 1992. - No. 2. - Art. 62. This law came into force upon its adoption, but was originally published on January 6, 1992 (in the Rossiyskaya Gazeta).

- visualrian.ru/ru/images/zooms/RIAN_468326.jpg

- . visualrian.ru. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- . visualrian.ru. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- Post of Russia.. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- In 1954, the dots were removed from the abbreviation RSFSR.

Literature

- State emblems and ensigns of the USSR and the allied Radyansky Socialist Republics: Set of posters / Author-director V.I. Stadnik, ed. N. G. Nesin, art. ed. Yu. G. Izhakevich, tech. ed. S. M. Skuratova, cor. N. M. Sidorova. - K.: Politvidav Ukraine, 1982. (Ukrainian)

| Coats of arms of the republics of the Soviet Union | |

| Azerbaijan SSR | Armenian SSR | Byelorussian SSR | Georgian SSR | Kazakh SSR | Kirghiz SSR | Latvian SSR | Lithuanian SSR | Moldavian SSR | RSFSR| Tajik SSR | Turkmen SSR | Uzbek SSR | Ukrainian SSR | Estonian SSR | |

An excerpt characterizing the Coat of Arms of the RSFSR

“No, there’s nothing you can do here,” Rostov thought, lowering his eyes, and was about to leave, but on the right side he felt a significant gaze directed at himself and looked back at him. Almost in the very corner, sitting on an overcoat with a thin, stern face, yellow as a skeleton, and an unshaven gray beard, sat an old soldier and stubbornly looked at Rostov. On the one hand, the old soldier’s neighbor whispered something to him, pointing at Rostov. Rostov realized that the old man intended to ask him for something. He came closer and saw that the old man had only one leg bent, and the other was not at all above the knee. Another neighbor of the old man, lying motionless with his head thrown back, quite far from him, was a young soldier with a waxy pallor on his snub-nosed face, still covered with freckles, and his eyes rolled back under his eyelids. Rostov looked at the snub-nosed soldier, and a chill ran down his spine.“But this one, it seems...” he turned to the paramedic.

“As asked, your honor,” said the old soldier with a trembling lower jaw. - It ended this morning. After all, they are also people, not dogs...

“I’ll send it now, they’ll clean it up, they’ll clean it up,” the paramedic said hastily. - Please, your honor.

“Let’s go, let’s go,” Rostov said hastily, and lowering his eyes and shrinking, trying to pass unnoticed through the ranks of those reproachful and envious eyes fixed on him, he left the room.

Having walked through the corridor, the paramedic led Rostov into the officers’ quarters, which consisted of three rooms with open doors. These rooms had beds; wounded and sick officers lay and sat on them. Some walked around the rooms in hospital gowns. The first person Rostov met in the officers' quarters was a small, thin man without an arm, in a cap and hospital gown with a bitten tube, walking in the first room. Rostov, peering at him, tried to remember where he saw him.

“This is where God brought us to meet,” said the little man. - Tushin, Tushin, remember he brought you near Shengraben? And they cut off a piece for me, so...,” he said, smiling, pointing to the empty sleeve of his robe. – Are you looking for Vasily Dmitrievich Denisov? - roommate! - he said, having found out who Rostov needed. - Here, here, and Tushin led him to another room, from which the laughter of several voices was heard.

“And how can they not only laugh, but live here?” thought Rostov, still hearing this smell of a dead body, which he had picked up in the soldier’s hospital, and still seeing around him these envious glances that followed him from both sides, and the face of this young soldier with his eyes rolled up.

Denisov, covering his head with a blanket, slept in bed, despite the fact that it was 12 o'clock in the afternoon.

“Ah, G”ostov? “It’s great, it’s great,” he shouted in the same voice as he used to do in the regiment; but Rostov noticed with sadness how, behind this habitual swagger and liveliness, some new bad, hidden feeling was peeking through. in facial expression, intonation and words of Denisov.

His wound, despite its insignificance, still had not healed, although six weeks had already passed since he was wounded. His face had the same pale swelling that was on all hospital faces. But this was not what struck Rostov; he was struck by the fact that Denisov seemed not to be happy with him and smiled at him unnaturally. Denisov did not ask about the regiment or the general course of the matter. When Rostov talked about this, Denisov did not listen.

Rostov even noticed that Denisov was unpleasant when he was reminded of the regiment and, in general, of that other, free life that was going on outside the hospital. He seemed to be trying to forget that former life and was only interested in his business with the supply officials. When Rostov asked what the situation was, he immediately took out from under his pillow the paper he had received from the commission and his rough answer to it. He perked up, starting to read his paper and especially let Rostov notice the barbs that he said to his enemies in this paper. Denisov’s hospital comrades, who had surrounded Rostov—a person newly arrived from the free world—began to disperse little by little as soon as Denisov began to read his paper. From their faces, Rostov realized that all these gentlemen had already heard this whole story, which had become boring to them, more than once. Only the neighbor on the bed, a fat lancer, sat on his bunk, frowning gloomily and smoking a pipe, and little Tushin, without an arm, continued to listen, shaking his head disapprovingly. In the middle of reading, the Ulan interrupted Denisov.

“But for me,” he said, turning to Rostov, “we just need to ask the sovereign for mercy.” Now, they say, the rewards will be great, and they will surely forgive...

- I have to ask the sovereign! - Denisov said in a voice to which he wanted to give the same energy and ardor, but which sounded useless irritability. - About what? If I were a robber, I would ask for mercy, otherwise I’m being judged for bringing robbers to light. Let them judge, I’m not afraid of anyone: I honestly served the Tsar and the Fatherland and did not steal! And demote me, and... Listen, I write to them directly, so I write: “if I were an embezzler...

“It’s cleverly written, to be sure,” said Tushin. But that’s not the point, Vasily Dmitrich,” he also turned to Rostov, “you have to submit, but Vasily Dmitrich doesn’t want to.” After all, the auditor told you that your business is bad.

“Well, let it be bad,” Denisov said. “The auditor wrote you a request,” Tushin continued, “and you need to sign it and send it with them.” They have it right (he pointed to Rostov) and they have a hand in the headquarters. You won't find a better case.

“But I said that I wouldn’t be mean,” Denisov interrupted and again continued reading his paper.

Rostov did not dare to persuade Denisov, although he instinctively felt that the path proposed by Tushin and other officers was the most correct, and although he would consider himself happy if he could help Denisov: he knew the inflexibility of Denisov’s will and his true ardor.

When the reading of Denisov’s poisonous papers, which lasted more than an hour, ended, Rostov said nothing, and in the saddest mood, in the company of Denisov’s hospital comrades again gathered around him, he spent the rest of the day talking about what he knew and listening to the stories of others . Denisov remained gloomily silent throughout the entire evening.

Late in the evening Rostov was getting ready to leave and asked Denisov if there would be any instructions?

“Yes, wait,” Denisov said, looked back at the officers and, taking out his papers from under the pillow, went to the window where he had an inkwell and sat down to write.

“It looks like you didn’t hit the butt with a whip,” he said, moving away from the window and handing Rostov a large envelope. “It was a request addressed to the sovereign, drawn up by an auditor, in which Denisov, without mentioning anything about the wines of the provision department, asked only for pardon.

“Tell me, apparently...” He didn’t finish and smiled a painfully false smile.

Having returned to the regiment and conveyed to the commander what the situation was with Denisov’s case, Rostov went to Tilsit with a letter to the sovereign.

On June 13, the French and Russian emperors gathered in Tilsit. Boris Drubetskoy asked the important person with whom he was a member to be included in the retinue appointed to be in Tilsit.

“Je voudrais voir le grand homme, [I would like to see a great man," he said, speaking about Napoleon, whom he, like everyone else, had always called Buonaparte.

– Vous parlez de Buonaparte? [Are you talking about Buonaparte?] - the general told him smiling.

Boris looked questioningly at his general and immediately realized that this was a joke test.

“Mon prince, je parle de l"empereur Napoleon, [Prince, I’m talking about Emperor Napoleon,] he answered. The general patted him on the shoulder with a smile.

“You will go far,” he told him and took him with him.

Boris was one of the few on the Neman on the day of the emperors' meeting; he saw the rafts with monograms, Napoleon's passage along the other bank past the French guard, he saw the thoughtful face of Emperor Alexander, while he sat silently in a tavern on the bank of the Neman, waiting for Napoleon's arrival; I saw how both emperors got into the boats and how Napoleon, having first landed on the raft, walked forward with quick steps and, meeting Alexander, gave him his hand, and how both disappeared into the pavilion. Since his entry into the higher worlds, Boris made himself a habit of carefully observing what was happening around him and recording it. During a meeting in Tilsit, he asked about the names of those persons who came with Napoleon, about the uniforms that they were wearing, and listened carefully to the words that were said by important persons. At the very time the emperors entered the pavilion, he looked at his watch and did not forget to look again at the time when Alexander left the pavilion. The meeting lasted an hour and fifty-three minutes: he wrote it down that evening among other facts that he believed were of historical significance. Since the emperor’s retinue was very small, for a person who valued success in his service, being in Tilsit during the meeting of the emperors was a very important matter, and Boris, once in Tilsit, felt that from that time his position was completely established. They not only knew him, but they took a closer look at him and got used to him. Twice he carried out orders for the sovereign himself, so that the sovereign knew him by sight, and all those close to him not only did not shy away from him, as before, considering him a new person, but would have been surprised if he had not been there.

The coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1925, on the pedestal of the monument to Vera Mukhina “Worker and Collective Farm Woman”. The sculptural group was created in 1937, the sculpture was reinstalled in 2009 on a new pavilion-pedestal specially erected for it. On the pedestal are the coats of arms of 10 union republics, but there should be 11. Armenia was unlucky.

The coat of arms was first described in Chapter XVII, Section 6, § 89, of the 1918 Constitution of the RSFSR.

“The coat of arms of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic consists of images on a red background in the rays of the sun of a golden sickle and hammer, placed crosswise with the handles downwards, surrounded by a crown of ears of ears and with the inscription: a) Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic b) Workers of all countries, unite !”

From May 11, 1925, the abbreviated name of the state began to be placed on the shield: “R.S.F.S.R.”, in accordance with the rules of the then spelling, and placed in the upper part of the shield, on each side of the shield-cartouche surrounded by 7 ears of corn , the motto was placed on a red ribbon at the bottom of the coat of arms.

In 1954, according to new spelling rules from the abbreviation “R. S.F.S.R.” points have been removed. It’s hard to say where this information comes from; there’s not a word about it in the 1956 rules of Russian spelling and punctuation.

On April 12, 1978, in connection with the adoption of the new Constitution, a five-pointed red star with a gold border was added above the shield.

Pavilion No. 1 “Central” at VDNKh. Until 1963 - “Chief”. Built in 1954. The abbreviation "R. S.F.S.R.” with dots and a five-pointed star at the same time?

Pavilion No. 67 “Karelia” at VDNKh. Until 1957 - “Karelo-Finnish SSR”, in 1957 - “Academy of Sciences of the USSR”, in 1958 - “Science”, in 1959-1963 - “Culture and Life of the Peoples of the RSFSR”, in 1964-1966 - “ Pulp, paper and wood chemical industry", hereinafter referred to as "Soviet Press". Built in 1954. The coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1925, is superimposed on top of the coat of arms of the Karelo-Finnish SSR.

Pavilion No. 59 “Grain” at VDNKh. The former pavilion of the Moscow, Ryazan and Tula regions, built in 1939. Coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1925.

Pavilion No. 64 “Optics” at VDNKh. In 1939-1941 - “Leningrad and the north-east of the RSFSR”, in 1954-1958 - “Leningrad and the north-west of the RSFSR”, in 1959-1966 - “Education in the USSR”, in 1967-1982 - “Economy” Agriculture". In 1937, reconstructed in 1954. Coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1954. No dots.

House of Culture at VDNKh. Built in 1954. Coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1954. No dots.

Russian Institute of Cultural Studies on Bersenevskaya Embankment. Tablet from the times of the Ministry of Culture of the RSFSR. Coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1978.

Delegatskaya street, house 3.

The coat of arms of the RSFSR, model 1925, on the building of the State Public Historical Library. Starosadsky lane, building 9, building 1.

Things definitely live a life of their own - the same coat of arms of the RSFSR on Istorichka - only now painted with gold paint.

Entrance doors of the high-rise building of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Smolenskaya Square. On the central door there are 8 coats of arms of the USSR, model 1946, and on two more doors - 8 pieces on each door - the coats of arms of the Union Republics. At that time, there were exactly 16 union republics within the USSR.

The lobby of the Dobryninskaya metro station.

Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts.

Moscow region. Serpukhov. Sovetskaya street, house 31/33. The former building of the Serpukhov Zemstvo Government.

Tver. Sovetskaya street, house 4. Now here is the Tver State Medical Academy. Coat of arms of the RSFSR with dots.