General characteristics of cognitive processes. Cognitive processes (perception, memory, thinking, imagination) are an integral part of any human activity and ensure one or another of its effectiveness. Cognitive processes allow a person to outline in advance goals, plans and the content of upcoming activities, play out in his mind the course of this activity, his actions and behavior, anticipate the results of his actions and manage them as they are performed.

When they talk about a person’s general abilities, they also mean the level of development and characteristic features of his cognitive processes, because the better these processes are developed in a person, the more capable he is, the greater capabilities he has. The ease and effectiveness of his learning depends on the level of development of the student’s cognitive processes.

A person is born with sufficiently developed inclinations for cognitive activity, but the newborn carries out cognitive processes at first unconsciously, instinctively. He has yet to develop his cognitive abilities and learn to manage them. Therefore, the level of development of a person’s cognitive abilities depends not only on the inclinations received at birth (although they play a significant role in the development of cognitive processes), but to a greater extent on the nature of the child’s upbringing in the family, at school, and on his own activities for the self-development of his intellectual abilities.

Cognitive processes are carried out in the form of separate cognitive actions, each of which represents an integral mental act, consisting inseparably of all types of mental processes. But one of them is usually the main one, the leading one, determining the nature of a given cognitive action. Only in this sense can mental processes such as perception, memory, thinking, and imagination be considered separately. Thus, in the processes of memorization and learning, thinking is involved in a more or less complex unity with speech; in addition, they are volitional operations, etc.

Character cognitive processes as individual property. The uneven development of different types of sensitivity is manifested in perception, memory, thinking, and imagination. This is evidenced, in particular, by the dependence of memorization on the method of learning (visual, auditory, kinesthetic-motor). For some people, it is effective to include vision when memorizing, and for others, when reproducing material. The situation is similar with the participation of hearing, kinesthesia

An important characteristic of the sensory organization of a person into a whole is sensitivity, which is part of the structure of temperament and abilities.

It is determined by a number of signs of the occurrence and course of sensorimotor reactions, regardless of which modality they belong to (visual, gustatory, etc.). These signs include, first of all, stable manifestations of the general rate of occurrence of sensorimotor reactions (speed of occurrence, duration of occurrence, aftereffect), psychomotor rhythm (method of switching from one type of sensory discrimination to another, smoothness or abruptness of the transition, in general - features of the temporary organization of sensorimotor acts) . Characteristic of one or another general method of sensitivity is the strength of the reaction with which a person responds to a wide variety of stimuli. The depth of sensitivity is judged by a combination of various indicators, especially by aftereffects in the form of trace reactions (immediate memory images, the formation of ideas and their associations). Sensitivity is inextricably linked with the type of emotionality: emotional excitability or inhibition, affectivity or inertia, monotony or multiplicity of emotional states when external conditions change, etc.

Sensitivity is a general, relatively stable personality trait that manifests itself in different conditions, under the influence of stimuli that are very different in nature (10, pp. 55-56).

Factors in the development of cognitive processes. Carrying out various types of activity, mental processes are formed in it.

Improving a child’s sensory perception is associated, firstly, with the ability to better use one’s sensory apparatus as a result of their exercise, and secondly, the ability to more and more meaningfully interpret sensory data plays a significant role, which is associated with the general mental development of the child. For a preschooler, the process of assimilation is involuntary; he remembers, since the material, as it were, settles in him. Imprinting is not a goal, but an involuntary product of the child’s activity: he repeats an action that attracts him or demands repetition of a story that interests him, not in order to remember it, but because it is interesting to him, and as a result he remembers. Memorization is built mainly on the basis of play as the main type of activity.

The main transformation in the functional development of memory that characterizes the first school age is the transformation of imprinting into a consciously directed process of memorization. At school age, memorization is restructured on the basis of learning. Memorization begins to proceed from certain tasks and goals and becomes a volitional process. Its organization also becomes different, planned: the division of material and its repetition are consciously used. The next significant point is the further restructuring of memory based on the abstract thinking developing in the child. The essence of memory restructuring in a schoolchild lies not so much in the transition from mechanical; memory to semantic, as much as in the restructuring of semantic memory itself, which acquires a more indirect and logical character. Children's imagination also first manifests itself and is formed in play, as well as in modeling, drawing, singing, etc. The actual creative and even combinatorial moments in the imagination are not so significant at first; they develop in the general process; mental development of the child. The first line in the development of imagination is increasing freedom in relation to perception. The second, even more significant, comes in later years. It lies in the fact that the imagination moves from subjective forms of fantasy to objectifying forms of creative imagination, embodied in objective products of creativity. If a teenager’s fantasy differs from children’s play in that it dispenses with its constructions without reference points in directly given, tangible objects of reality, then mature creative imagination differs from youthful fantasy in that it is embodied in objective, tangible for others, products of creative activity. An essential prerequisite for the development of a healthy, fruitful imagination is the expansion and enrichment of the student’s experience. It is also important to familiarize him with new aspects of objective reality, which, based on his narrow everyday experience, should seem unusual to him; It is necessary for the child to feel that the unusual can also be real, otherwise the child’s imagination will be timid and stereotypical. It is very important to develop in a child the ability to criticize and, in particular, a critical attitude towards himself, towards his own thoughts, otherwise his imagination will only be a fantasy. The student should be taught to include his imagination in academic work, in real activities, and not turn into idle fantasy divorced from life, creating only a smokescreen from life. Thought processes are primarily carried out as subordinate components of some “practical” (at least in a child’s play) external activity, and only then thinking is distinguished as a special, relatively independent “theoretical” cognitive activity. As a child, in the process of systematic learning, begins to master any subject - arithmetic, natural science, geography, history, i.e., a body of knowledge, albeit elementary, but built in the form of a system, the child’s thinking inevitably begins to be restructured. The construction of a system of knowledge of any scientific subject presupposes the dismemberment of what in perception is often fused, fused, but not significantly connected with each other, the selection of homogeneous properties that are essentially interconnected. In the process of mastering the subject content of knowledge built on new principles, the child forms and develops forms of rational activity characteristic of scientific thinking. Thinking acquires new content - the systematized and more or less generalized content of experience. Systematized and generalized experience, and not isolated situations, becomes the main support base for his mental operations.

In the first period of systematic schooling, mastering the first foundations of the knowledge system, the child enters the realm of abstraction. He penetrates into it and overcomes the difficulties of generalization, moving simultaneously from two sides - from the general to the particular, and from the particular to the general. In the learning process, scientific concepts are mastered. Mastering a system of theoretical knowledge during training, a child at this highest stage of development learns to “investigate the nature of the concepts themselves,” revealing through their relationships their increasingly abstract properties; empirical in its content, rational in form, thinking turns into theoretical thinking in abstract concepts (216, p. 180, 271-398).

Attention as the main condition for the implementation of the cognitive process. Attention does not act as an independent process. Both in self-observation and in external observation it is revealed as the direction, disposition and concentration of any mental activity on its object, only as a side or property of this activity.

Attention does not have its own, separate and specific product. Its result is the improvement of any activity to which it is attached (59, p. 88).

Involuntary attention is established and maintained independently of a person's conscious intention. Voluntary attention is consciously directed and regulated attention, in which the subject consciously chooses the object to which it is directed. Voluntary attention develops from involuntary attention. At the same time, voluntary attention turns into involuntary, no longer requiring special efforts. Involuntary attention is usually due to immediate interest. Voluntary attention is required where there is no such immediate interest, and we make a conscious effort to direct our attention in accordance with the tasks that confront us, with the goals that we set.

The development of attention in children occurs in the process of learning and upbringing. Crucial for the organization of attention is the ability to set a task and motivate it in such a way that it is accepted by the subject (2t6, pp. 448-457).

Attention and control. Every human action has an orientation, an executive and a control part. Control is a necessary and essential part of action management. Control activities do not have a separate product; they are always aimed at something that, at least partially, already exists or is created by other processes.

Attention is such a control function. A separate act of attention is formed only when the action of control becomes mental and reduced. The process of control, carried out as a detailed objective activity, is only what it is, and is by no means attention. On the contrary, he himself requires the attention that has developed by this time. But when the new action of control becomes mental and contracted, then and only then does it become attention. Not all control is attention, but all attention is control.

Control only evaluates the activity or its result, and attention improves them. How does attention, if it is mental control, give not only an assessment, but also an improvement in activity? This occurs due to the fact that control is carried out using a criterion, measure, sample, and the presence of such a sample, a “preliminary image,” creating the possibility of a clearer comparison and distinction, leads to a much better recognition of phenomena. The use of a sample explains two main properties of attention - its selectivity (which, therefore, does not always express interest) and its positive influence on any activity with which it is associated.

Voluntary attention is planned attention. This is control over action, carried out on the basis of pre-established criteria and methods of their application. Involuntary attention is also control, but control that goes beyond what in an object or situation “is striking itself.” Both the route and the means of control here do not follow a predetermined plan, but are dictated by the object (59, pp. 89-93).

Formation attention. To form a new act of voluntary attention, we must, along with the main activity, give the task of checking it, indicate for this the criterion and techniques, the general path and sequence. All this must first be given in an external sense, that is, one should begin not with attention, but with the organization of control as a specific, external, objective action. And then this action, through step-by-step development, is brought to a mental, generalized, abbreviated and automated form, when it turns into an act of attention that meets the new task.

The formation of stable attention can be carried out by mastering control according to stage-by-stage formation, starting with a materialized form, then in loud speech and, finally, in the form of external speech to oneself. After this, control acquires its final form among schoolchildren in the form of an act of attention.

In this case, two difficulties may arise. The first is that the action being performed can prematurely escape control, and therefore control loses its clear, generalized and strictly constant form of execution and becomes unstable. The second difficulty is that the orienting and executive parts of the action may diverge, and while the executive part does one job (for example, dividing a word into syllables, etc.), the orienting part (for example, speaking out loud) outlines the other.

These difficulties must be taken into account when learning to control actions during their gradual formation.

As a result of the gradual formation of control (over text, pattern, arrangement of figures, etc.), this objective action becomes ideal (the action of gaze) and is added to the main action being performed (writing, reading, etc.). Directed towards the main action being performed, control now seems to merge with it and imparts its characteristics to it - focus on the main action and concentration on it, i.e. the usual characteristics of attention (59, pp. 80-85, 93-94).

Attention and performance. Children vary significantly in terms of volume, stability and distribution of attention. In general, attentive children learn better, but in inattentive children, academic performance is more related to indicators of voluntary attention, especially with its distribution. The low level of development of this property of attention limits children’s capabilities when performing educational tasks. Therefore, training the distribution of attention can help improve academic performance.

A high level of development of voluntary attention is a necessary condition for the implementation of other factors of successful learning, in particular individual motor tempo. Moreover, the higher the individual pace of attentive students, the better they learn. And for inattentive students, a high individual pace can be combined with low performance.

Math performance is particularly influenced by attention span and individual pace. Sustained attention may correlate with low math ability. Academic performance in the Russian language is more influenced by the level of development of distribution of attention and less influenced by the volume of attention. Reading success is most associated with stability of attention, which ensures the accuracy of recreating the sound form of words (165, pp. 42-43).

Moving on to the consideration of individual cognitive processes, we note that, of course, any cognitive process is carried out in a cognitive action, in which other cognitive processes are present in an explicit or hidden (unconscious) form. However, each of the cognitive processes has its own area of application, its own methods of implementation, and its own characteristics. Therefore, they can and should be studied separately from each other, and not in the unity in which they are actually presented in the mental life of a person.

Sensations and perception

Feel. Sensations are a reflection of the qualities of things, mediated by the activity of the senses; reflection of a separate sensory quality or undifferentiated and non-objectified impressions of the environment.

The physiological state of the sensory organ is reflected primarily in the phenomena of adaptation, in the adaptation of the organ to a long-term stimulus; This adaptation is expressed in a change in sensitivity - its decrease or increase. An example is the fact of rapid adaptation to one long-lasting odor, while other odors continue to be felt as acutely as before.

The phenomenon of contrast, which is reflected in a change in sensitivity under the influence of a previous (or accompanying) stimulus, is also closely related to adaptation. Thus, due to contrast, the sensation of sour is intensified after the sensation of sweet, the sensation of cold after hot, etc. It should also be noted that the receptors have the property of delaying sensations, which is expressed in a more or less long aftereffect of stimuli. Just as a sensation does not immediately reach its final meaning, it does not immediately disappear after the cessation of irritation. Thanks to the delay in the rapid succession of stimuli one after another, the merging of individual sensations into a single, coherent whole occurs, as, for example, in the perception of melodies, films, etc. (217, p. 93; 216, p. 185, 191).

A qualitative characteristic of a sensation is its modality, that is, the specificity of each type of sensation in comparison with others, determined by the physicochemical characteristics of those stimuli that are adequate for a given analyzer. Such specific modal characteristics, for example, of visual sensation are, as is known, color tone, lightness and saturation, and auditory - pitch, loudness and timbre, tactile - hardness, smoothness, roughness, etc.

In all types of sensations, modal characteristics are organically interconnected with spatiotemporal characteristics. In addition, an important empirical characteristic of sensation is its intensity (45, pp. 154-159).

Thresholds of sensations. Not every stimulus causes a sensation. It may be so weak that it does not cause any sensation. We do not hear many vibrations of the bodies around us, we do not see with the naked eye many changes occurring around us. A known minimum intensity of the stimulus is required to produce a sensation. This minimum intensity of stimulation is called the “lower absolute threshold”. The sensitivity of the receptor is expressed by a value inversely proportional to the threshold.

Along with the lower one, there is also an “upper absolute threshold,” i.e., the maximum intensity possible for the sensation of a given quality. These thresholds are different for different types of sensations. Within the same species, they can be different in different people, in the same person at different times, under different conditions.

The question of whether there is a sensation of a certain type at all (visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory, tactile, temperature, pain, sensation of position and movement, etc.) inevitably follows the question of the conditions for distinguishing stimuli. It turned out that, along with absolute ones, there are “thresholds of discrimination.” A certain ratio between the intensities of two stimuli is required for them to produce different sensations.

One and the same person simultaneously has many forms of absolute and distinctive sensitivity, unevenly developed and different from each other in level. Thus, the same person may have increased differential sensitivity in the field of spatial vision or speech hearing and at the same time decreased sensitivity of color vision or musical hearing. Often, especially with one-sided development and early specialization of a person, contradictions arise between different types of sensitivity.

Sensitivity thresholds shift significantly depending on a person’s attitude to the task that he solves using certain sensory data. The same physical stimulus of a certain intensity can be both below and above the threshold of sensitivity and, thus, be or not be noticed depending on what significance it acquires for a person: whether it appears as an indifferent moment of the environment for a given individual or becomes an indicator of the essential conditions of its activity (216, pp. 188-192; 10, pp. 54-55).

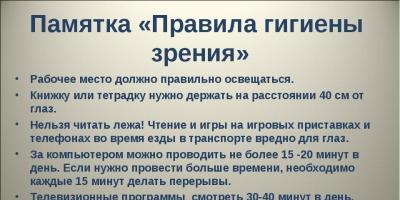

Hygiene of the senses in school settings. The conditions in which activities are carried out - lighting and coloring of the room, its equipment, sound pressure level, degree of convenience of the workplace and the rationality of the working posture - are not at all indifferent to students, either favoring performance or causing its decline.

The level of illumination is extremely important for performance and also affects the quality of work performed by students. Visual acuity at illumination equal to 30 OK, begins to decline after the first lesson and by the fifth it drops by 22% compared to the morning level. If the classes were held at illumination of 100 OK, then the visual acuity of the same schoolchildren increased from the first to the third lesson, but the decrease by the end of classes did not reach the initial, morning level. During all hours of study, the indicators of stability of clear vision under fluorescent lighting were higher than during the same hours under incandescent lighting.

In addition to sufficient illumination of workplaces, evenly diffused lighting of classrooms has the most beneficial effect on performance. Blinding and flickering light has an extremely adverse effect not only on visual functions, but also on the state of the cardiovascular system.

The painting of the premises and equipment - furniture, work equipment - is important for the performance of schoolchildren. Light, warm colors with the same power of light sources greatly increase the level of illumination in the premises and already have a positive effect on performance. In addition, color and color play a well-known psychogenic role. At the same time of day, with the same window orientation and wall color, in a classroom with light-colored furniture, the illumination is 20% higher than in classrooms with desks painted black and brown. A better state of visual function and a positive psychological effect were noted in cases where students copied and read texts written with yellow chalk on a green blackboard: their visibility increased by an average of 11%, while after working with a black board and white chalk - only 0.1%.

Along with the improvement of visual functions, due to the increase in room illumination, hearing acuity increases in children and adolescents, which also favors performance. Schoolchildren have noticed a decrease in performance due to an increase in outdoor and indoor air temperatures. Attention, the ability to remember, and the speed of mental calculation are inversely proportional to the outside temperature: they worsen as the temperature rises and improve as it decreases; The best time for studying is considered to be autumn and winter. High temperatures in classrooms (up to 26°) lead to tension in thermoregulatory processes and a sharp decrease in the mental performance of students by the end of the lesson. When training sessions are held at a comfortable room temperature (18-20°), which is ensured by air exchange depending on the outside temperature, the number of errors in the measured work of schoolchildren at the end of the lessons increased by 27-34%, while in uncomfortable conditions it reached 57-82 %.

It is known that in closed, poorly ventilated rooms, simultaneously with an increase in air temperature, its physicochemical properties sharply deteriorate. The deterioration of the physical and chemical properties of air, especially in low rooms, entails a significant deterioration in performance.

Changes in the functional state of the central nervous system appear in students under the influence of “school noise.” The noise intensity level in lessons is mainly in the range from 50 to 80 dB, with a frequency from 500 to 2000 Hz Noise up to 40 dB does not cause negative changes in the functional state of the central nervous system. Changes become pronounced when exposed to noise at 50 and 60 dB. Solving arithmetic examples required a noise level of 50 dB by 15-55%, and at 60 dB- 81-105% more time than before exposure to noise. With noise at 65 dB schoolchildren showed a decrease in attention by 12-16%.

The correspondence of educational equipment (desks, tables, chairs, etc.) to the length and proportions of the body of children and adolescents is the main condition that ensures the ability to maintain the least tiring working posture and reproduce the most economical movements. However, even when the dimensions of equipment and furniture correspond to height, prolonged forced positioning of the body causes fatigue and negatively affects performance. Regulated straight and bent postures at a desk are the most tiring. Often this can be aggravated by the irrational shape of classrooms, which requires a different arrangement of furniture than usual - a large number of rows and a reduction in the distance from the blackboard to the first desks (18, pp. 109-127).

Perception. The work of the sense organs and the corresponding subjective images - sensations - form the basis of perception. Perception arises as a result of the synthesis of sensations with the help of ideas and existing experience, that is, it is a synthesis of the objective with the help of the subjective (44, p. 5).

In everyday life there are two sharply differentiated meanings of the words “see”, respectively, “hear”.

One meaning can be illustrated by the following example: “From here I see the spine of the book, but from here I don’t see it.” The word “see” in the first meaning means to have a visual image of the corresponding object. In order to see in this sense, it is enough to open your eyes, to have healthy vision, it is enough that the object is not too far away and not too dimly lit, so that it is not blocked by another object.

If the visual image does not adequately convey the subject, we talk about a visual illusion. Visual illusions refer to visual perception covered by this first meaning of the word "see".

Another meaning of the word “see” can be explained by the following examples: “The trouble is, he doesn’t see proportions!”, “This artist sees color perfectly.” In order to “see” in this sense, it is not enough to have even a clear visual image. In this sense, one can be able to “see” or not. The ability to “see” can and should be taught.

The word “see” means the ability to make a visual judgment based on the additional work of the eye. If the content of a visual judgment is inadequate to the object, this does not at all indicate the presence of an illusion. In most cases, the inadequacy of visual judgment to an object is an error. Like any error, it can be shown and corrected by another visual judgment based on the same image. Several visual judgments about the same thing usually differ from each other quite significantly, while the underlying visual image may be unchanged.

The visual image arises as a whole without our desire. Visual judgments are guided by perceptual tasks: they produce selective work. By focusing on one thing in an object, they thereby renounce the other. The contents of a visual judgment always have a certain degree of abstraction and therefore are easily transferred for comparison to other objects, easily leading, in the end, to full-fledged generalizations.

The image is first truly understood only as a result of a chain of visual judgments based on it. What we call perception in the true, human sense of the word is not immediate passive reflection, completed in the bare reality of the image, but the process of meaningful active sensory cognition of an object on the basis of its image (48, pp. 382-383).

Human perception is a unity of the sensual and logical, sensual and semantic, sensation and thinking.

When perceiving, a person not only sees, but also looks, not only hears, but also listens, and sometimes not only looks, but also examines or peers, not only listens, but also listens. Therefore, any somewhat complex perception is essentially a solution to a certain problem, which proceeds from certain sensory data revealed in the process of perception in order to interpret them. The activity of interpretation is involved in every meaningful human perception.

Constancy of perception is expressed in the relative constancy of the size, shape and color of objects when the conditions of their perception vary within certain limits (216, pp. 241-254). Perception and thinking. There are both similarities and differences between solving a perceptual problem and solving a mental problem. In both cases, you have to look for a hypothesis that would explain the observed facts, in both cases there are elegant and inelegant solutions, in both cases the solution often comes unexpectedly, like a sudden insight. However, perceptual problem solving usually occurs super-fast, it is unconscious and not expressed verbally (this does not mean that thinking always occurs slowly, consciously and is expressed verbally, but often this is still the case or partly so); it does not seem to require the strict motivation that demonstrative thinking requires; Unlike most difficult problems of thinking, in perception the correct result is almost always achieved; and finally, solving a perceptual problem results in a perception rather than an idea.

It can be said that perception is unreasonable in one respect. We often perceive phenomena not as we know them, or we perceive what we know very well as unlikely or simply impossible. What is perceived may at times contradict what is known about the situation.

Perception is an active process that involves learning. Hunters can recognize birds from incredible distances in flight, and they are able to use small differences to identify objects that look the same to other people. The same thing occurs when doctors look at x-rays or microscopic slides to look for signs of pathology. There is no doubt that perceptual learning takes place in this case, but we still do not know exactly how far the influence of learning on perception extends.

A brick and a piece of explosive may look and feel very similar, but they will “behave” very differently. We usually define objects not by their appearance, but rather by their purpose or by their basic properties. A table can have different shapes, but it is an object on which other objects can be placed; it can be square or round, but still remain a table. In order for the perception to correspond to the object, that is, to be “true,” it is necessary that our expectations be justified (19a, p. 240, 246-247).

Recognition and its types. In the process of perception, a person solves various problems of recognizing objects and phenomena.

The most elementary form of recognition is more or less automatic recognition in action. It manifests itself in the form of an adequate reaction to a familiar stimulus. The next step is recognition, associated with a feeling of familiarity, but without the possibility of identifying a recognized object with a previously perceived one. Finally, the highest level of recognition is the identification of the object of perception with an object perceived earlier (21b, pp. 302-303).

The last stage of the recognition process is usually called recognition. With the help of identification, a person solves two types of problems:

1. It is known that the object of identification belongs to a certain set and some other object belongs to the same set. It is necessary to establish whether the object of recognition is connected with this object by some specific relationship (relationship recognition tasks). For example: “Is a pyramid ABCD correct?”, “Is this wall painted green?”.

2. It is known that the object of identification belongs to a certain set, and a certain set of objects belonging to the same set is given. It is necessary to find the one with which the identified object is connected by the specified relationship (object recognition tasks). For example: “In what case is the highlighted noun in the sentence: “My friend and I live very happily together”?” or: “Who is depicted in this portrait?”

According to the method of solving problems, identification problems are divided into two types:

1) problems solved using feature testing (the first questions of the examples given). The process of solving these problems occurs successively, unfolded over time; 2) problems solved by comparison with some standard (second questions of the given examples). The process of solving these problems occurs simultaneously (almost instantly) (252, pp. 104-107).

With the successive method of identification, an element-by-element examination of the object is carried out, the gradual selection (detection) of identifying features is carried out, and the next choice occurs after the previous one has been assessed.

The simultaneous method proceeds according to a previously established, proven program, which is determined by the characteristics of the standard (81, pp. 143-144).

Observation. Forming, expanding and deepening in the process of purposeful activity, practical action, play, etc., perception itself eventually turns into the independent activity of observation. Just as sensation is included in perception, so perception is included in the process of active observation (216, pp. 276-279).

Observation is meaningful, interpretive and goal-directed perception.

At different stages of development of observation in a child, the following changes: a) the content available for interpretation and the depth of cognitive penetration into it, b) the complexity of the composition that can be grasped by the child as a whole, in the unity and interconnection of all its parts, c) consciousness, plannedness, systematicity of the observation process itself.

At the first stage in the development of observation, with limited experience and knowledge, interpretation is based not so much on connections and cause-and-effect dependencies between phenomena, but on their similarity (similar interpretation). As the child’s knowledge expands and his thinking develops, along with the likening one, he develops an inferential interpretation, which initially comes primarily from external, sensory properties, random, but more or less familiar combinations, connections, relationships. Finally, the third stage in the development of observation is formed by inferential interpretation, which reveals the already abstract, sensory data, internal properties of objects and phenomena in their essential relationships.

A change in the content of observation and the depth of cognitive penetration into it is also associated with a change in the form of perception. From a schematic, undivided whole, the child’s perception and observation moves to a whole based first on the external and then on the internal interconnection of its parts, sides, and moments. The degree of conscious observation also changes. First, at the stage of assimilating interpretation, the child surrenders more or less uncontrollably to the power of the first, more or less accidental, interpretation. Then a rethinking of individual moments of the situation or sometimes even the entire situation as a whole begins to appear as a result of an unintentionally arising comparison of its various moments. Finally, at the highest levels, the child learns to consciously check the interpretation of what he perceives that arises in him in more or less systematically organized observation (217, pp. 108-114).

Development of perception. The eye is a family of organs designed to perceive space, time, movement, speed, acceleration, color and light, the shape of objects, surface texture, i.e., almost all perceptual categories from which the image of the visible world is built. He can perceive them together, separately, in different sequences. Is this perception ensured only by the structure of the eye itself, or must the individual learn to do this, i.e., he himself can and should organize and reorganize his own and preferably holistic perception of the world? Science leans towards the second answer.

The structure of the eye is fundamentally the same for all people. And the image of the same world, constructed with the help of the eye, can be completely different among people. Direct perspective in the painting of the Italian Renaissance and reverse perspective in ancient Russian icons are evidence of different ways of seeing, and not just images of the artist’s world. The same is observed in science, where different types of spaces have their own name and surname: the spaces of Euclid, Riemann, Lobachevsky, Minkowski, Einstein.

The maturation of the anatomical and physiological apparatus of the eye ends by the age of 15-16 years. Under conditions of sensory deprivation, maturation slows down or stops altogether. It is known that cataract removal for a person born blind does not ensure full development of vision if the operation is performed in adulthood. And the development of vision and perception of the world continues throughout active life (84, pp. 15-18).

Sensory learning involves the assimilation of systems of sensory standards developed by society, which include, for example, the generally accepted scale of musical sounds, the grid of phonemes of various languages, systems of geometric shapes, etc. Such standards become operational units of perception and mediate the child’s perceptual actions in the same way as how his practical activity is mediated by a tool, and his mental activity by words (81, p. 113).

Memory

Memorization, recollection, reproduction, recognition, which are included in memory, are built on the basis of the elementary ability to imprint and - under appropriate conditions - restore sensitivity data, but are in no way reduced to it. These are specific processes in which thinking is essentially included in a complex and contradictory unity with speech, attention, interests, emotions, etc. (216, p. 285).

Memorization. The focus on memorization alone does not give the desired effect. Its absence can be compensated for by high forms of intellectual activity, even if this activity itself was not aimed at memorization. Only the combination of a focus on memorization and high forms of intellectual activity really creates a solid foundation for the most successful memorization and makes memorization productive.

In order to achieve a sufficient memorization effect, it is necessary that the student not only set himself the goal of remembering the material, but also have effective means for this. This means that even voluntary memorization should be included in an activity that, due to the very nature of its implementation (the intellectual activity it requires), would lead to successful memorization.

What is remembered best is what arises as an obstacle or difficulty in activity. Memorizing material given in ready-made form is carried out with less success than memorizing material found independently in the course of active activity. - What is remembered, even involuntarily, but in the process of active intellectual activity, is retained in memory more firmly than what is was remembered arbitrarily, but under normal conditions of performing a mnemonic task (225, p. 23- 334).

Supports for memorization. Both with immediate and delayed reproduction, the result of memorization is higher when relying on visual, figurative material. However, memorization productivity when relying on words increases with age more than when relying on pictures. Therefore, the difference in the use of both supports decreases with age. When you come up with your own, verbal supports become a more effective means of memorization than ready-made pictures.

In a broad sense, the support of memorization can be everything with which we associate what we remember or what itself “pops up” in us as associated with it. The semantic support is a certain point, that is, something short, compressed, serving as a support for some broader content, replacing it. Semantic support points differ from associative “supports”. The most developed form of semantic support points are theses, as a brief expression of the main idea of each section. More often, section titles serve as a reference point. A special type of support points are questions about the content of the read part.

The next type of support points are images of what is said in the text. Examples, vivid digital data, comparisons - all this can often be used as supporting points. This should also include titles, names, special terms, some especially vivid and characteristic epithets, sometimes simply unfamiliar or less familiar words or individual, stand-out expressions.

As reproduction is delayed, the positive role of the plan increases. The material is forgotten less in cases where the supporting points were highlighted during the memorization process. The strength of a strong point depends on how deeply and thoroughly we understand the content of the section thanks to it. The semantic support point is the support point of understanding. For us, it is not the strongholds themselves that are important, but the mental activity that is necessary to highlight them.

Isolating strong points is a recoding of the material, just as its subsequent reproduction is decoding, restoration of what has been memorized using the code created during the memorization process (225, pp. 214-397).

Memorization and repetition. For memorization productivity, variety of repetition is essential. It makes it possible to take a fresh look at the material that has already been perceived, to highlight in it what was not highlighted before, and in accordance with the new tasks that are set before each subsequent repetition, to direct memorization each time along a strictly defined path. It is natural, therefore, that standard imprinting of material gives a much smaller effect than memorization, which includes varied, modifying repetition. It is necessary to organize repetition so that it always contains something new, and does not represent a simple restoration of what has already happened. It is important that repetition is included in a new activity (in solving a new problem) as its necessary link, as the basis for solving a new problem, as a means of solving it (225, pp. 339-340).

Memorization and understanding. Memory focus can have different effects on our understanding of what we remember. In some cases, it can interfere with understanding, obscure the need to understand what is being learned, and lead to rote memorization. In other cases, the focus on memorization, especially the consciously set task of remembering, has a positive effect on understanding and acts as a stimulus for a more complete, deep and accurate understanding. Memorization based on understanding is in all cases certainly more productive than memorization not based on understanding (225, p. 336).

Memorization is mechanical. The more mechanical the memorization, the more literal the reproduction. Hardly accessible material creates a strong tendency to remember literally. Children, more often than adults, cannot comprehend what they learn, and therefore the tendency towards literal reproduction is observed in them more often than in adulthood.

The requirements for memorization accuracy are sometimes understood by students themselves as the need to learn by heart or almost by heart. The literalness of reproduction, the insufficiency of transmission “in one’s own words” is largely explained by the fact that the child often does not have enough “one’s own words” (225, pp. 151-153).

Memorization. The universality of memorization as a means of learning is explained by the fact that for its use it is not necessary to disclose the features of the material being studied. Knowledge is introduced into the inner world of the student only according to the logic of external consistency, which explains the low productivity of this activity (58, p. 9).

A significant increase in learning ability falls between the ages of 8 and 10 years and especially increases from 11 to 13 years. From the age of 13, there is a relative decline in the rate of memory development. New growth begins at age 16. At the age of 20-25 years, the memory of a person engaged in mental work reaches its highest level (216, p. 318).

Methods of learning. Methods of memorization include semantic grouping of material, highlighting semantic support points, semantic correlation or comparison of what is remembered with something already known.

It is not so much the plan itself, but the process of drawing it up that plays an important role in memorization. The same applies to the meaning of intermediate, auxiliary links, connections between the known and the unknown, to which we resort in order to facilitate memorization. And in this case, it is not so much these links themselves, but the process of their formation that serves as the basis for memorization (225, p. 337).

Methods of random learning. Can a student, when solving a mnemonic problem in relation to new material, independently analyze and generalize it?

To answer this question, the following experiment was conducted: two groups of students were given the task of independently mastering educational material that was new to them based on the same text given to them. At the same time, the first group of students (IV experimental class of school No. 17 in Kharkov) was previously trained in ways to voluntarily memorize text, while the second group of students (VI class of a regular school) did not undergo such training.

In the first group, students correctly understood the task (not just remember the material, but assimilate it) and therefore used the previously learned method of classifying the material as a method of memorization to assimilate it. These students identified the logical structure of the text as the subject of memorization.

In the second group, students, as a subject of memorization, focused only on the speech forms of the text, i.e., what was given directly in the text itself. This is understandable, because if students do not have the means to highlight and analyze the logical structure of the text, it cannot act as a special subject of their activity, and, consequently, a subject of memorization.

As a result, 76% of students in the first group and only 35% of the second group correctly learned the given text during direct reproduction, and 81% of students in the first group (even more than with direct reproduction) and 33% of the second group during delayed reproduction.

The results of this experiment showed that only if students have specially developed methods of voluntary memorization that are adequate to the presented material, the mnemonic task is considered as a task for the logical analysis of this material, for identifying internal, necessary relationships between the form of the material and its content. In the absence of such methods, students’ memorization is aimed primarily at the form of the material (in particular, the speech form) without proper penetration into the content (210, pp. 33-41).

Recalling words. Recalling the right word or the name of the corresponding object depends on at least two factors. One of these is the frequency with which a given word occurs in a given language and in the subject's past experiences. Familiar words are recalled much easier than relatively rare words. The second factor is the inclusion of a word in a certain category. Words denoting things of a certain category are recalled more easily than words that do not have a categorical nature (159, p. 111).

Memory. A memory is a representation related to a more or less precisely defined moment in the history of our life. It is only thanks to him that we do not each time find ourselves alienated from ourselves, from what we ourselves were at the previous moment of our life (216, p. 306).

The entire attractive power of memories lies in the living reproduction, recreation of previously experienced relationships, in transferring them from the past to the present and projecting them into the future. It is no coincidence that memories often turn into dreams. This most often occurs outside of a person’s conscious intentions. Memories, like dreams and interests of an individual, can act as a special form of satisfying a person’s need for desired experiences (72, pp. 184-187).

Performance. A representation is a reproduced image of an object based on our past experience. While perception gives us an image of an object only in the immediate presence of this object, representation is an image of an object that is reproduced in the absence of the object.

Representations can have varying degrees of generality; they form an entire stepwise hierarchy. On the one hand, the most generalized of them turn into concepts, but, on the other hand, in the images of memories, representations reproduce former perceptions in their uniqueness (216, pp. 287-289).

Reproduction and mental activity. We not only reproduce less of what is in the original, but at the same time allow various qualitative changes in the original;

1) generalization or “condensation” of what is given in the original in a specific, expanded, detailed form; 2) specification and detailing of what is given in a more general or condensed form;

3) replacement of one content with another, equivalent in meaning;

4) mixing or moving individual parts of the original;

5) the unification of what is given separately from each other, and the separation of what is interconnected in the original; 6) additions that go beyond the original; 7) distortion of the semantic content of the original as a whole or its individual parts.

Analysis of the changes observed during reproduction shows that all of them, with the exception of the distortion of the original, are the result of mental processing of what was perceived. It is this mental activity that constitutes the psychological core of reproduction. However, it is incorrect to attribute restructuring during reproduction only to the reproduction itself. During the period of forgetting, many changes also occur, which are then discovered during reproduction.

In fact, the traces left from what is perceived do not disappear. They also “live” in a period of forgetting, and the source of their “life” is precisely the mental activity carried out at this time. New thought processes occurring in this period, aimed at something new, can stand in one way or another, at least indirectly, in connection with what was perceived earlier and thereby serve as a source of its change (225, p. 157 -162).

Reminiscence. Reminiscence is a phenomenon when the reproduction of what has been memorized over time not only does not deteriorate, but improves. It is associated primarily with internal work to comprehend the memorized material and master it. Reminiscence is most clearly revealed on material that arouses interest.

Essential for the manifestation of reminiscence is the extent to which the learner has mastered the content of the material. If he has not mastered the content of the material to some extent, the latter is quickly forgotten and reminiscence usually does not occur.

If in the process of immediate reproduction the learner tries to restore the material, using largely external associative connections, then during more delayed reproduction the subject relies mainly on semantic connections (216, p. 313).

Forms of involuntary memory in younger schoolchildren. Forms of involuntary memory of third grade schoolchildren were identified in the process of students completing a task to analyze a concept that was new to them. The result revealed that approximately 20% of students were able to correctly accept the task, hold it, fulfill the given goal of the action, and at the same time involuntarily remember and reproduce the content of the theoretical material.

Approximately 50-60% of schoolchildren redefined the task in accordance with their interests in new facts. They involuntarily remembered and reproduced only the factual material of the task and therefore did not solve the proposed problem consciously enough.

Finally, the third group of schoolchildren (approximately 20-30%) were unable to correctly retain the task in their memory, involuntarily remembered only individual fragments of factual material, and they solved the problem unconsciously.

Thus, by the end of primary school age, three qualitatively different forms of involuntary memory develop. Only one of them ensures meaningful and systematic memorization of educational material. The other two, which appear in more than 80% of schoolchildren, give an unstable mnemonic effect, largely dependent on the characteristics of the material or on stereotypical methods of action, and not on the actual tasks of the activity (211, pp. 52-53).

Features of voluntary memory of primary schoolchildren. The intention to remember this or that material does not yet determine the content of the mnemonic task that the subject has to solve. To do this, he must highlight a specific subject of memorization in the object (text), which represents a special task. Some schoolchildren highlight the cognitive content of the text as such a goal of memorization (about 20% of third grade schoolchildren), others highlight its plot (23%), and still others do not highlight a specific subject of memorization at all. Thus, the task is transformed into different mnemonic tasks, which can be explained by differences in learning motivation and the level of formation of goal-setting mechanisms.

Only in the case when the student is able to independently determine the content of a mnemonic task, find adequate means of transforming the material and consciously control their use, can we talk about mnemonic activity that is arbitrary in all its links. About 10% of students are at this level of memory development by the time they graduate from primary school. Approximately the same number of schoolchildren independently determine a mnemonic task, but do not yet fully know how to solve it. The remaining 80% of schoolchildren either do not understand the mnemonic task at all, or it is imposed on them by the content of the material.

Any attempts to ensure the development of memory in different ways without the real formation of self-regulation (primarily goal setting) give an unstable effect. Solving the problem of memory in primary school age is possible only with the systematic formation of all components of educational activity

(211, p. 55-57).

The role of mnemonic abilities in learning knowledge. In the structure of memory, two types of mnemonic abilities can be distinguished, which have different physiological mechanisms: the ability to imprint and the ability to process information semantically. Both types of mnemonic abilities influence the success of knowledge acquisition, but a major role is played by the ability to process information, which characterizes the close unity of the processes of memory and thinking.

The proportion of the ability to imprint turns out to be different when mastering different school subjects. If for such subjects as the Russian language, chemistry, geometry, geography, the role of this ability turns out to be significant, then for mastering courses in literature, history and algebra, the influence of the ability to imprint does not appear (73, pp. 58-61).

Purposeful development of memory in learning. Purposeful development of memory during the learning process is carried out in connection with the solution of a special class of problems.

The first group of tasks of this class includes tasks of organizing everyday educational and everyday behavior. Consciousness of mastering the work and rest schedule can be ensured already in primary schoolchildren and teenagers by introducing office equipment: calendars, diaries, work plans, weeklies, etc. The schedule, becoming an indirect form of managing the time of one’s life, creates the “effect of the presence” of the future in current behavior and leads to a higher level of functioning of forms of memory in everyday behavior.

The second group of educational tasks that ensure the development of memory is associated with the need to isolate and isolate the actual mnemonic and reproductive actions in educational activities and with the possibility of conscious control over their implementation. To do this, it is necessary, in the learning process, to create and change forms of cooperation between children in solving various educational tasks (for example, mutual control). The initial form of such cooperation is the joint activity of children, shared with the teacher. In the future, the most suitable form is the form of independent productive work of students with texts based on the use of written language and visual means (composing fairy tales, stories).

The third group of educational tasks is associated with the formation and mastery of developed structures of the mnemonic and reproductive nature of actions in a certain subject content. Mastering the system of transforming educational material in order to prepare it for reproduction is based on the use of various tools (matrices, diagrams, plans, etc.). In the lower grades, these means should be directly related to the content of the subject of memorization and reproduction and gradually take on an increasingly generalized nature. In the elementary grades, you can initially use a drawing, with the help of which the child can select and organize the subject content of the text in order to reproduce it, or use speech plans with the help of dramatization, and only then move on to drawing up oral or written plans (161, p. 239- 246).

Initially, the child has a predominant figurative memory, the importance of which decreases with age. Nevertheless, the result of memorization is usually higher when relying on visual material, so the widespread use of visual teaching aids in school is natural and effective.

With the development of verbal memory, the productivity of memorization when relying on words increases. High memorization productivity is observed in cases where it is included in activities that require intellectual activity. Therefore, it is better to remember what is associated with independent searches for solutions and overcoming difficulties - for example, in problem-based learning. Schoolchildren are less successful in remembering material given to them in ready-made form.

The effectiveness of memorization depends on the ways of organizing mnemonic activity. Memorization, common in school, becomes unproductive when it follows the logic of a purely external sequence of presentation, given in a textbook or by a teacher, without independently revealing the features of the material being studied. It is useful for students, with the help of a teacher, to master such methods of memorization as semantic grouping of material, highlighting strong points, semantic correlation of what is remembered with what is already known and learned. Educational material is better remembered, in particular, if the student himself, in the process of memorization, identifies strong points - titles of sections of the text, examples, vivid digital data, special terms, images, etc.

Perception

Perception in preschool age loses its initially affective character: perceptual and emotional processes are differentiated. Perception becomes meaningful, purposeful, and analytical. It highlights voluntary actions - observation, examination, search.

The process of development of children's perception in preschool age was studied in detail by L.A. Wenger. According to Wenger, the basis of perception is perceptual actions. Their quality depends on the child’s assimilation of systems of perceptual standards. Such standards for the perception of, for example, shapes are geometric figures, for the perception of color - the spectral range, for the perception of sizes - the physical quantities adopted for their assessment.

Stages of formation of perceptual actions. Perceptual actions are formed in learning, and their development goes through a number of stages. The process of their formation (the first stage) begins with practical, material actions performed with unfamiliar objects. This stage poses new perceptual tasks for the child. At this stage, the necessary corrections necessary to form an adequate image are made directly into material actions. The best results of perception are obtained when the child is offered for comparison so-called sensory standards, which also appear in external, material form. With them, the child has the opportunity to compare the perceived object in the process of working with it.

At the second stage, the sensory processes themselves, restructured under the influence of practical activity, become perceptual actions. Perceptual actions are now carried out with the help of receptor apparatus and anticipate the implementation of practical actions with perceived objects. At this stage, children become familiar with the spatial properties of objects with the help of extensive orienting and exploratory movements of the hand and eye.

At the third stage, perceptual actions become even more hidden, collapsed, reduced, their external effector links disappear, and perception from the outside begins to seem like a passive process. In fact, this process is still active, but it occurs internally, mainly only in the consciousness and on a subconscious level in the child.

The role of visual components in perception. The development of the perception process in preschool age allows children to quickly recognize the properties of objects that interest them, distinguish some objects from others, and clarify the connections and relationships that exist between them. At the same time, the figurative principle, very strong in this period, often prevents the child from drawing correct conclusions regarding what he observes. In J. Bruner's experiments, many preschoolers correctly judge the conservation of the amount of water in glasses when water is poured from one glass to another behind a screen. But when the screen is removed and the children see a change in the water level in the glasses (achieved due to the different base areas of the glasses), direct perception leads to an error: the children say that there is less water in the glass where the water level is lower. In general, in preschoolers, perception and thinking are so closely connected that they speak of visual-figurative thinking, which is most characteristic of this age.

Attention

The attention of a child of early preschool age is involuntary. It is evoked by visually attractive objects, events and people and remains focused as long as the child retains a direct interest in the perceived objects.

At the stage of transition from involuntary to voluntary attention, the means that control the child’s attention are important. Reasoning out loud helps a child develop voluntary attention. If a 4-5 year old preschooler is asked to constantly name out loud what he should keep in the sphere of his attention, then the child will be quite able to voluntarily and for quite a long time maintain his attention on certain objects or their details.

From younger to older preschool age, children's attention progresses simultaneously along many different characteristics. Younger preschoolers usually look at pictures that are attractive to them for no more than 6-8 s, while older preschoolers are able to focus on the same image for 12 to 20 s. The same applies to the time spent doing the same activity for children of different ages. In preschool childhood, significant individual differences are already observed in the degree of stability of attention in different children, which probably depends on the type of their nervous activity, physical condition and living conditions. Nervous and sick children are more often distracted than calm and healthy children, and the difference in the stability of their attention can reach one and a half to two times.

Preschool childhood is the age most favorable for memory development.

Memory at this age acquires a dominant function among other cognitive processes. Neither before nor after this period does the child remember the most varied material with such ease.

Types of memory. The memory of a preschooler has a number of specific features. In younger preschoolers, memory is involuntary. The child does not set a goal to remember or remember something and does not have special methods of memorization. Events, actions, and images that are interesting to him are easily imprinted, and verbal material is also involuntarily remembered if it evokes an emotional response. The child quickly remembers poems, especially those that are perfect in form: sonority, rhythm and adjacent rhymes are important in them. Fairy tales, short stories, and dialogues from films are remembered when the child empathizes with their characters.

During preschool age, the efficiency of involuntary memorization increases. In children of early preschool age, involuntary visual-emotional memory dominates. In some cases, linguistically or musically gifted children also have well-developed auditory memory.

Children of primary and middle preschool age have well-developed mechanical memory. Children easily remember and reproduce without much effort what they saw or heard, but only if it aroused their interest and the children themselves were interested in remembering or remembering something. Thanks to such memory, preschoolers quickly improve their speech and learn to use household items.

The more meaningful the material a child remembers, the better the memorization. Semantic memory develops along with mechanical memory, so it cannot be assumed that in preschoolers who repeat someone else’s text with great accuracy, mechanical memory predominates. With active mental work, children remember material better than without such work.

The first recollection of impressions received in early childhood usually occurs around the age of three years (meaning adult memories associated with childhood). It has been found that almost 75% of children's first recalls occur between the ages of three and four years. This means that by this age, i.e., by the beginning of early preschool childhood, the child has developed long-term memory and its basic mechanisms.

In middle preschool age (between 4 and 5 years), voluntary memory begins to form. Improving voluntary memory in preschoolers is closely related to setting them special tasks for memorizing, preserving and reproducing material. Many such tasks arise in gaming activities, so games provide the child with rich opportunities for memory development. Children as young as 3-4 years old can voluntarily memorize, remember and recall material in games.

Stages of formation of arbitrary memory. 3. M. Istomina analyzed how the process of developing voluntary memorization occurs in preschoolers. In primary and middle preschool age, memorization and reproduction are involuntary. In older preschool age, there is a gradual transition from involuntary to voluntary memorization and reproduction of material.

The transition from involuntary to voluntary memory includes two stages.

At the first stage, the necessary motivation is formed, i.e. the desire to remember or remember something. At the second stage, the mnemonic actions and operations necessary for this arise and are improved.

In the initial stages, conscious, purposeful memorization and recollection appear only sporadically. Usually they are included in other types of activities, since they are needed both in play, and when running errands for adults, and during classes - preparing children for school.

Children's memory productivity in play is much higher than outside of it. By playing, it is easier for a child to reproduce difficult-to-memorize material. Let's say, having taken on the role of a seller, he is able to remember and recall at the right time a long list of products and other goods. If you give him a similar list of words outside of a game situation, he will not be able to cope with this task.

In order for the transition to voluntary memorization to become possible, special perceptual actions must appear aimed at better remembering, more fully and more accurately reproducing the material retained in memory. The first special perceptual actions are distinguished in the activities of a 5-6 year old child, and most often they use simple repetition for memorization. By the age of 6-7 years, the process of voluntary memorization can be considered formed. Its psychological sign is the child’s desire to discover and use logical connections in the material for memorization.

Features of mnemonic processes. It is believed that with age, the speed at which information is retrieved from long-term memory and transferred to working memory, as well as the volume and duration of working memory, increases. It has been established that a three-year-old child can operate with only one unit of information currently located in RAM, and a fifteen-year-old child can operate with seven such units.

With age, the child’s ability to evaluate the capabilities of his own memory develops, and the older the children, the better they can do this. Over time, the strategies for memorizing and reproducing material that the child uses become more diverse and flexible. Of 12 pictures presented, a 4-year-old child, for example, recognizes all 12, but is able to reproduce only two or three, while a 10-year-old child, having recognized all the pictures, is able to reproduce 8 of them.

Imagination

The beginning of the development of children's imagination is associated with the end of early childhood, when the child first demonstrates the ability to replace some objects with others and use some objects in the role of others (symbolic function). Imagination is further developed in games, where symbolic substitutions are made quite often and using a variety of means and techniques.

Types of imagination. In the first half of preschool childhood, the child’s reproductive imagination predominates, mechanically reproducing received impressions in the form of images. These can be impressions received by the child as a result of direct perception of reality, listening to stories, fairy tales, or watching films. Imaginative images of this type restore reality not on an intellectual, but on an emotional basis. The images usually reproduce something that made an emotional impression on the child, caused him to have very specific emotional reactions, and turned out to be especially interesting. In general, the imagination of preschool children is still quite weak.

The younger preschooler is not yet able to completely restore the picture from memory, dismember and then creatively use the individual parts of what he perceived as fragments from which something new can be put together. Younger preschoolers are characterized by the inability to imagine things from a point of view different from their own, from a different angle. If you ask a six-year-old child to arrange objects on one part of the plane in the same way as they are located on another part of it, turned to the first at an angle of 90°, this usually causes great difficulties for children of this age. It is difficult for them to mentally transform not only spatial, but also simple planar images.

In older preschool age, when voluntary memorization appears, the imagination turns from reproductive, mechanically reproducing reality into creative imagination. The main type of activity where children's creative imagination is manifested is role-playing games.

Cognitive imagination is formed by separating the image from the object and designating the image using a word. Affective imagination develops as a result of the child’s awareness of his “I”, psychological separation of himself from other people and from the actions he performs.

Functions of the imagination. Thanks to the cognitive-intellectual function of imagination, the child learns better about the world around him and solves the problems that arise before him more easily and successfully. Imagination in children also plays an affective and protective role. It protects the child’s easily vulnerable and weakly protected soul from excessively difficult experiences and traumas. The emotional-protective role of imagination is that through an imaginary situation, tension can be discharged and a unique, symbolic resolution of conflicts can occur, which is difficult to achieve with the help of real practical actions.

Stages of imagination development. Imagination, like any other mental activity, goes through a certain development path in human ontogenesis. O.M. Dyachenko showed that children's imagination in its development is subject to the same laws that other mental processes follow. Just like perception, memory and attention, imagination from involuntary (passive) becomes voluntary (active), gradually turns from direct to mediated, and the main tool for mastering it on the part of the child is sensory standards.

The initial stage in the development of imagination can be attributed to 2.5-3 years. It is at this time that imagination, as a direct and involuntary reaction to a situation, begins to turn into a voluntary process and is divided into cognitive and affective.

The development of cognitive imagination is associated with the process of “objectifying” the image through action. Through this process, the child learns to manage his images, change and clarify them, and regulate his imagination. However, he is not yet able to plan it, to draw up a program of upcoming actions in his mind in advance. This ability appears in children only at 4-5 years of age.

The development of affective imagination from the age of 2.5-3 years to 4-5 years goes through a number of stages. At the first stage, negative emotional experiences in children are symbolically expressed in the characters of the fairy tales they hear. At the second stage, the child can already build imaginary situations that remove threats to his “I” (stories - children’s fantasies about themselves as supposedly possessing especially pronounced positive qualities). At the third stage, a projection mechanism is formed, thanks to which unpleasant knowledge about oneself, one’s own unacceptable qualities and actions begin to be attributed by the child to other people, surrounding objects and animals. By the age of about 6-7 years, the development of affective imagination in children reaches a level where many of them are able to imagine and live in an imaginary world.

By the end of the preschool period of childhood, the child’s imagination is presented in two main forms:

A) arbitrary, independent generation of an idea by a child;

B) the emergence of an imaginary plan for its implementation.

Thinking

The main lines of development of thinking in preschool childhood can be outlined as follows:

Further improvement of visual and effective thinking based on developing imagination;

Improving visual-figurative thinking based on voluntary and indirect memory;

The beginning of the active formation of verbal-logical thinking through the use of speech as a means of setting and solving intellectual problems.

Stages of development of thinking. N.N. Poddyakov identified six stages of development of thinking from junior to senior preschool age. These steps are as follows.

1. The child is not yet able to act in his mind, but is already capable of using his hands, manipulating things, to solve problems in a visual and effective way.

2. In the process of solving a problem, the child has already included speech, but he uses it only to name objects with which he manipulates in a visually effective manner. Basically, the child still solves problems “with his hands and eyes,” although he can formulate the result of the practical action performed in verbal form.

3. The problem is solved figuratively through the manipulation of images of objects. Here the ways of performing actions aimed at solving the task are realized and can be verbally indicated. An elementary form of reasoning aloud arises, not yet separated from the performance of real practical action.

4. The child solves the problem according to a previously drawn up and internally presented plan. It is based on memory and experience accumulated in the process of previous attempts to solve similar problems.

5. The problem is solved internally (in the mind), followed by the implementation of the same task in a visually-effective manner in order to reinforce the answer found in the mind and then formulate it in words.

6. The solution to the problem is carried out only in the internal plan with the issuance of a ready-made verbal solution without subsequent recourse to practical actions with objects.

An important conclusion that was made by Poddyakov is that in children the stages passed in the development of mental actions do not completely disappear, but are transformed and replaced by more advanced ones. Children's intelligence at this age functions on the basis of the principle of consistency. It presents and, if necessary, simultaneously includes in the work all types and levels of thinking: visual-effective, visual-figurative and verbal-logical.

Conditions of mental activity. Despite the peculiar childish logic, preschoolers can reason correctly and solve quite complex problems. Correct answers can be obtained from them under certain conditions.